Are oil paintings just the selfies of yore?

Insider #158 with "Ways of Seeing" the "Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction"

Dear reader,

Are oil paintings and selfies basically the same thing? Are memes the true art of humankind? Let’s find out.

The SneakyArt (Insider) Post is written to address deeper questions and existential quandaries from my journey as an artist and writer. This work is made possible by the paying subscribers and patrons of this newsletter.

Am I reading too much? Do I understand too little? Is this dangerous? Is it fun? Are open-ended questions much better than definitive answers? If yes, read on.

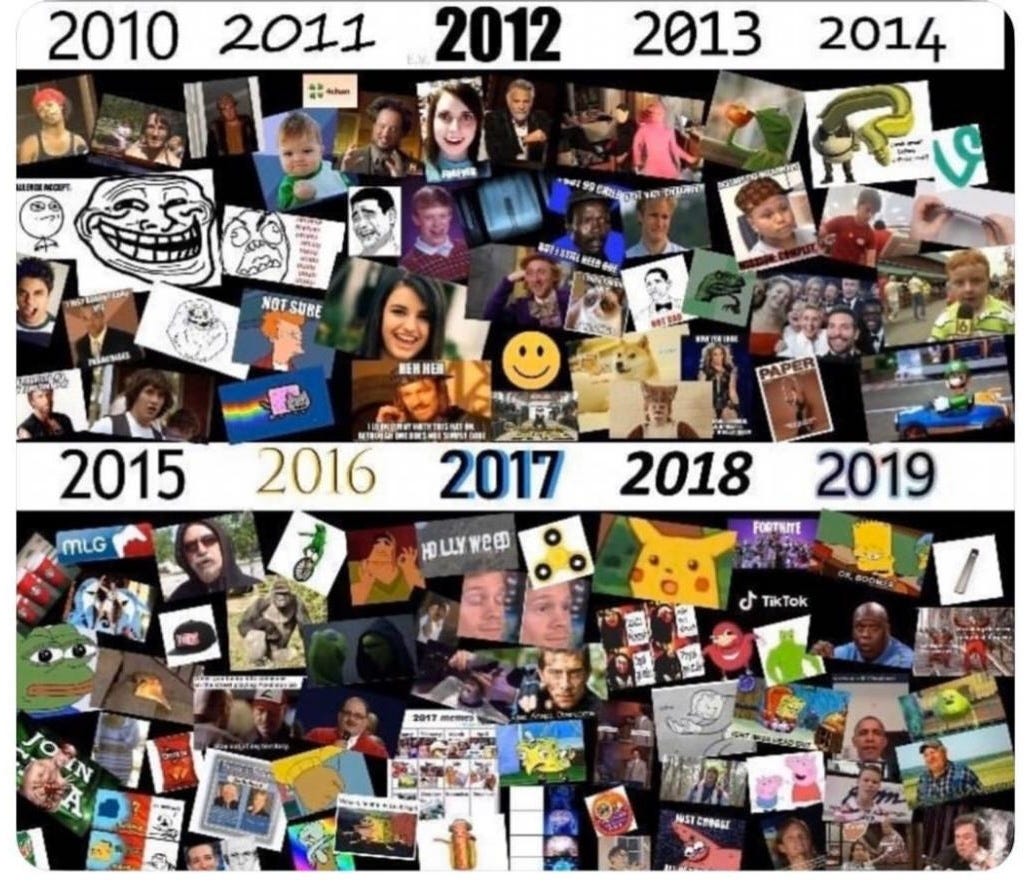

It begins with a Meme

In the early 2010s, memes started spreading all over the internet. I was immediately fascinated - that a character or scene from a film, tv show, or advertisement in one part of the world could make sense to someone in another part of the world, that an image could be so definitive of a mood/feeling/vibe that it transcended borders of nationality, language, and pop culture.

Memes were culture, rapidly multiplying and shared back and forth until there was no clear beginning or end. Memes were the language of the global internet. Memes supplanted hegemony by shattering every stranglehold over the image.

But then, roughly ten years ago, oligarchs started to claw back autocratic control over the world-wild internet. Nothing looks today like it used to then, nothing of today is where things were headed back then.

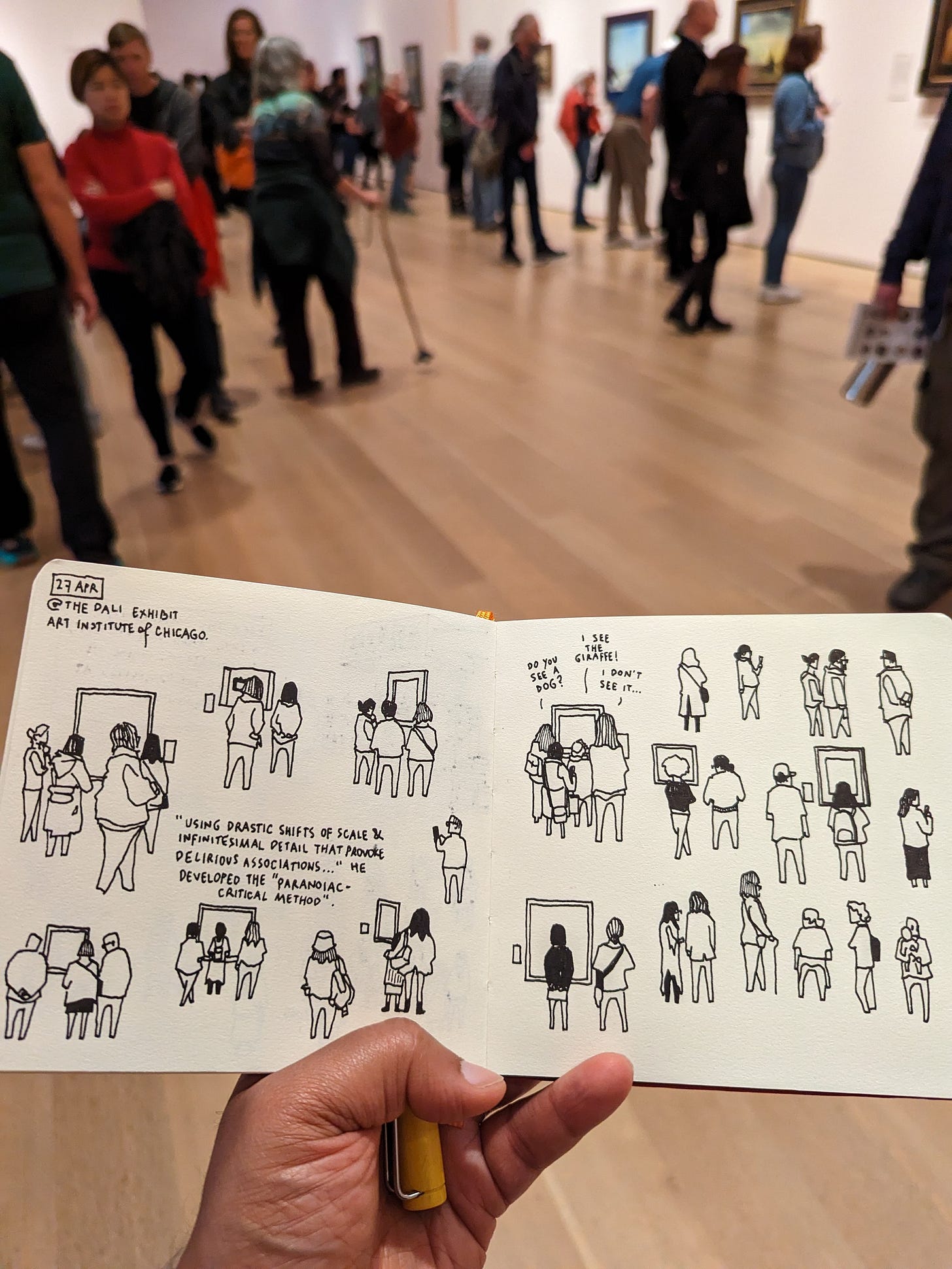

Starry Night Thinking

A couple of years ago, after giving me a lovely tour of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, dear friend Samantha Dion Baker left me alone to draw. I walked up and down, and through all the rooms, until I was sitting on a bench, a little distance from one of the most famous paintings in the world. Drawing the crowd around it, this question popped into my head -

To a generation that has already seen everything on their screens, what is the purpose of art in a museum? What sets apart the physical confrontation?

When I shared this thought, I got the best kind of answer from Meg Conley - “Aura!” she responded. It was the best answer because it led me down a rabbit-hole to an essay by Walter Benjamin - The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. And that gave me many things to think about.

When you see Starry Night by van Gogh from the side, you can the layers of paint on it. You know you are within touching distance of the literal canvas he used, and those paints, and those brush-strokes. That inimitable feeling is aura. But it is also the uniqueness of a piece of art arising from its historicity - its connection to art history and the traditions it follows and predates, and also its more literal being in a particular space (say, a church) over a period of time (say, four hundred years).

It is this aura that is shattered by the technological ability to make infinite reproductions. Its connection to history is broken. It is cut off from tradition. It loses the quasi-religious value of belonging only to a particular space, where everyone must visit in order to see it.

In his 1936 essay, Walter Benjamin wondered about the effects of prints and illustrations to art, what gramophones do to the experience of music, and what films were (then) starting to change about the art of dramatic performance.

Reader, do you visit the theater? How would you compare the experience of a play to a movie screening? What about live music vs using speakers at home?

Now, after reading John Berger’s Ways of Seeing (free to read), I have another answer to my original question - What sets apart the physical confrontation?

Benjamin wrote about the impact of technology on how we experience art, and the role it plays in our world. Berger, while referencing Benjamin in the first essay, for the most part thinks about how art connects with class and capitalism.

“Today we see the art of the past as nobody saw it before.” - John Berger

Benjamin spoke about the historicity of art, but Berger holds a more skeptical view, pointing to the financialization of art and the business of art-history, sustained by a symbiotic relationship between curators, art historians, art dealers, and owners.

Berger writes about the tradition of oil painting as a means to commission an image in a world where images were a rare and precious commodity. The act of commissioning a painting, of owning and displaying it one’s home, was a kind of bragging rights. The job of the oil-painter of the European tradition then was to supply images in the burgeoning open art market for clients who wished to possess and project an image of themselves - of affluence, exoticity, adventure, spirituality, or desirability.

So … selfies, right?

So …

To a generation that has already seen everything on their screens, what is the purpose of art in a museum? What sets apart the physical confrontation?

Both Benjamin and Berger already talk about this.

Benjamin speaks about how art, freed from its original narrative, will splinter to form new narratives with every new reproduction.

Berger talks about art as humankind’s inheritance, not a financial tool for capitalism. He stresses the importance of personal relationships with art that are not mediated by the narratives of museums and art critics. His final essay is about advertisements (which he terms ‘publicity’), and how oil painting as possession correlates with publicity as cultivation of desire, or the possibility of possession.

So, I think about what the visitors at the MoMA are doing, and I wonder if their behaviour would change without their phones. I think about how much time anyone spends in any single room at the MoMA versus average time spent at the gift shop. Is the museum only an advertisement for the items in the gift shop? Does the history of human art displayed on those walls only serve to sell tote bags and posters and Mondriaan Rubik’s Cubes? It may sound incredible but this is the face of capitalism. For instance, did you read that article about how the New York Times is actually just a gaming company?

Perhaps visitors to a museum come for aura. Maybe just to witness it. Maybe to take a splinter of aura back with them. Maybe selfies are what oil paintings used to be, just a whole lot easier with modern technology. And maybe the meme is the real power of humankind, not in service to anyone, an end in itself. Art for art’s sake.

Support the audacity of this blasphemy by becoming a paying subscriber.

Thank you for reading.

I remember that day well!