Consciousness is a Vivid Theatre of Imagination

thoughts about free will from watching Rohan do things.

Dear reader,

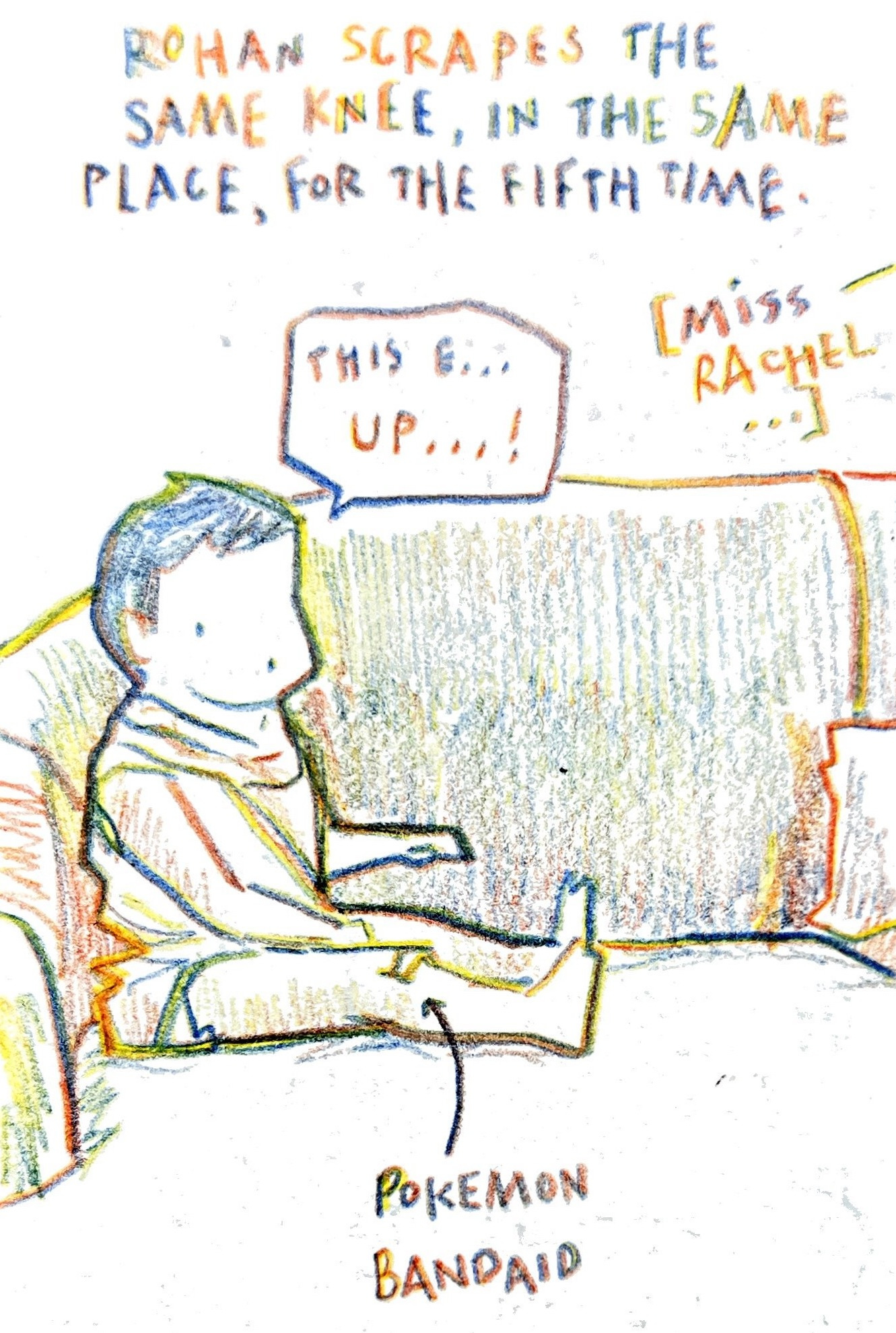

Rohan wants the TV every time he hurts himself. He manages to hurt himself a lot. He wants the TV when he is upset. Mote, he cries out, pointing to the remote. He wants to see Miss Rachel. It works like magic, but he also wants the TV when he eats. And before he sleeps. Putting him to sleep is an hour’s exercise when things go well, because he does not like being asleep. He has a strong sense of FOMO. Struggling against sleep and demanding we switch the light back on, inevitably he reaches the point of being over-tired. Then he is angry at not being asleep. Silly Rohan!

But we cannot blame his for these things. He is just a baby. He doesn’t know any better.

In today’s post, what it means to know better.

The SneakyArt (Insider) Post is written for paying subscribers and patrons of this newsletter. Every now and then, I share behind-the-scenes progress on various projects, and deeper thoughts from my journey as an artist and writer.

Grab the summer offer to become a SneakyArt Insider!

Free Will. So What?

Earlier this year at the Aspen Ideas Festival, I attended a talk by physicist Brian Greene about science, the nature of the universe, and free will. Or the lack of it. There is no scientific basis for believing in free will, he said. He closed his talk with the thought that, regardless of absolute reality, every person still needs to believe in free will, because it’s the only good way to live.

Walking out of the hall, I wondered about the point of such a debate if the conclusion was already agreed upon. This week, I am reading about the philosopher Henri Bergson and thinking about free will again. I also listened to this episode of the Philosophize This podcast, and it has left me thinking differently about the debate around free will.

A hundred years ago, humans believed that machines with mechanical and electrical connections would soon replicate human consciousness. They failed and a lot of modern philosophy, including that of Bergson, was formulated in response. Today, we believe in lines of code. The growing consensus among physicists, Silicon Valley billionaires, and people-who-professionally-talk-about-things, is that free will does not exist. Sam Altman believes his kids will never be smarter than AI, meaning to make the claim for everyone’s kids.

But if we do not have free will, can anyone be punished for a crime? How do we attribute blame, or personal accountability? Did Rohan not shatter the glass front of the expensive TV table? Or does the blame lie with us, buying vulnerable furniture when the boy is getting up on his feet and testing his strength on things? Can any person be rewarded for great success, or penalized for great failures? Like deciding to have a child in our mid-thirties? Like forgetting Rohan’s passport at home, realizing at the airport, but getting away with it because apparently no one demands identification for children under two years?

Does a lack of belief in free will require a radical re-structuring of modern society, of crime and punishment, of reward and penalty? You may not care for this debate, but we are already in the middle of it. It is part of how we think of disease, for example. The evolution of thought from blame and fault to suffering and misfortune. Of genetics and predispositions. The idea of addiction as a disease, not human weakness. Of alcoholism, for example, as a slippery slope one is unable to escape. Of poverty as systemic failure.

There are great semantics at play. Such as, a person suffering from autism, not an autistic person. Not homeless, but unhoused. Much of human communication and perception is semantics. All politics is semantics. So, semantics matter very much.

Of the human with certain characteristics imposed upon them by forces larger than themselves. Where does free will sit inside this model? Is the road to empathy paved by deterministic ideas?

Or, will it never be Rohan’s fault?

I jump back to Bergson:

“Consciousness seems proportionate to the living being’s power of choice. It lights up the zone of potentialities that surrounds the act. It fills the interval between what is done and what might be done.”

Bergson, according to author Will Durant, argues that we tend to think in terms of space, but time is as fundamental as space, and holds the essence of life and perhaps all reality. That time is an accumulation, a growth, a duration.1

And this:

“Doubtless we think with only a small part of our past; but it is with our entire past … that we desire, will, and act.”

Will Durant’s book is almost exactly 100 years old. A lot of the ideas have been refuted since then. A lot of his arguments are a product of his time. He may have blind spots that do not occur to me. My field of known-unknowns is growing, but the field of unknown-unknowns is so vast. To read him is, therefore, risky business.

But he is a truly beautiful writer. I highly recommend The Story of Philosophy, if you have never read it:

“(Consciousness) is no useless appendage; it is a vivid theatre of imagination, where alternative responses are pictured and tested before the irrevocable choice... Free will is a corollary of consciousness; to say that we are free is merely to mean that we know what we are doing.” - Will Durant.

Rohan, I suppose, does not know what he is doing.

According to one idea of free will, humans are distinguished from animals (or babies, I suppose) by their higher-order volitions. A first-order volition is a base desire for something. A higher-order volition is a desire about another desire. To watch Miss Rachel is his first-order volition. To desire good sleep, and therefore not fall prey to YouTube at bed-time, is a higher-order volition.

I will have to wait at least until Rohan’s higher-order volitions kick in.

Reader, do addictive algorithms reduce us to our first-order volitions? Do they effectively make animals of us? Do they wreck our consciousness and steal our free will?

“The Story of Philosophy” (1926) by Will Durant

My mother (I’m 63) used to read Will and Ariel Durant and was a big fan. It really brings me back. I did some rereading recently myself. I am a physicist and I do believe in free will.

I'm perplexed and somewhat amused by the idea that, if we don't have free will, that has significant implications for how we as a society should treat criminals, etc. Does it?

The criminal doesn't have free will in deciding whether or not to commit the crime... but we somehow have free will in determining how to handle the criminal? Or, for that matter, in deciding whether or not we have free will?

In a world without free will, why wouldn't how we handle crime be just as predetermined as the crime itself?

Like Brian Greene, I'll choose to believe in free will. If I'm right, then it was wise for me to believe in it. If I'm wrong, then I didn't have the free will to choose otherwise.