This post is a bonus commentary in both audio and (summarized) text format. We will cover -

📝 A brief history of war reportage

💡 Some ideas from Episode 15 of the podcast with George Butler

🗺 The recently concluded War in Afghanistan (text)

⚡ Announcement

I would like to invite you to the SneakyArt Discord server. I have found Discord to be the best place to build a community over common interests. The SneakyArt Discord is a private space for my top listeners, readers, supporters, and subscribers. I am there quite often, and it’s the best place to get in touch with me directly.

⚔ Art about War

Art about war has been around for as long as both art and war. To begin, it was not reportage in any sense, although it was meant to carry a specific message for a specific population. It was more like propaganda or foreign policy.

At the turn of the 2nd century AD, the Roman emperor Trajan launched a military campaign against the Dacian Empire. As news of his exploits trickled to Rome, the stories were added - as a spiraling comic-strip - to a 126-ft marble pillar called Trajan’s Column. Check out this fascinating virtual guided tour on NatGeo for more.

The first instance of war-reportage was in the 1850s during the Crimean War. Newspapers were already a new thing, but this one - The Illustrated London News - was doing something completely new again. Taking advantage of the latest tech, it was using woodblock lithographic printing to print illustrations with the text.

Newspapers had made it possible to share information quickly from any corner of the world. People wanted to know what was happening overseas in the farthest reaches of the British empire.

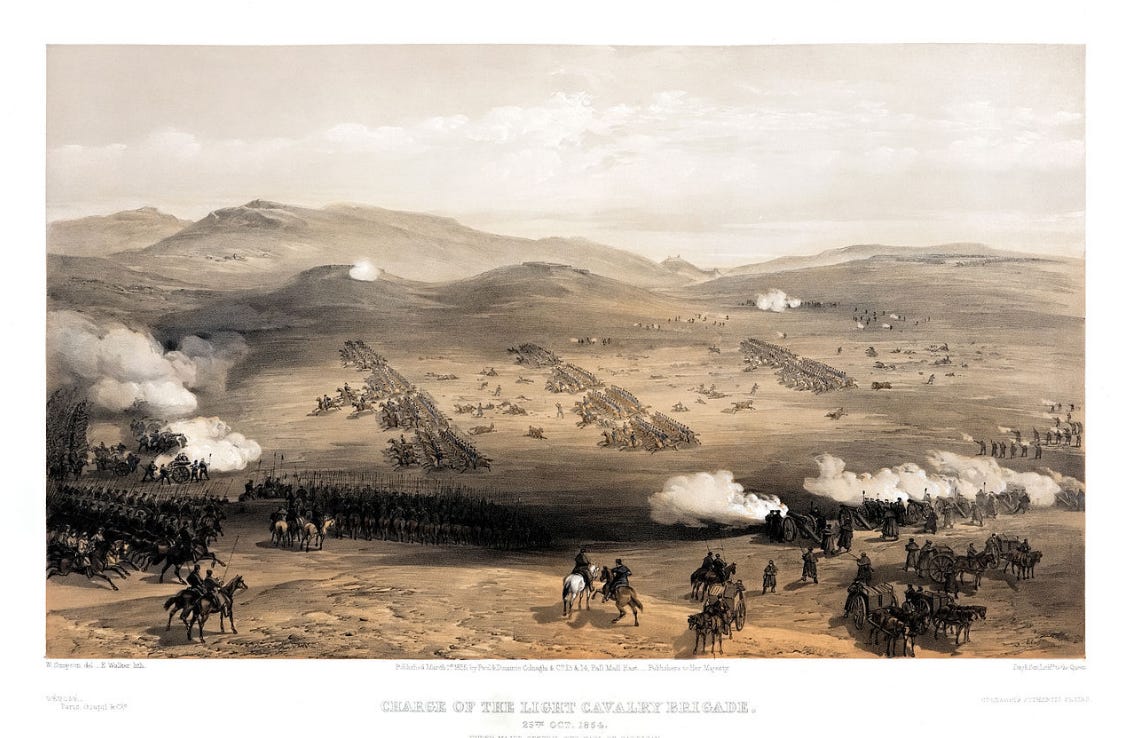

An illustrator, William Simpson, was sent to gather images of the brave soldiers in the Crimean peninsula. His first task was to paint the famous scene later immortalized in Lord Tennyson's poem, The Charge of the Light Brigade.

Listen to the audio in this post for a longer discussion on reportage, its incentives, and and the circumstances around its inception.

Drawn Across Borders

But war reportage is not exactly what George Butler does. He paints scenes around a war, lives affected by war, and places destroyed by war. As we discuss in our conversation, his objective is to provide wider context to geo-political conflicts in terms of the toll they take on innocent human life. We spoke about this work, and how he has brought together a decade of art in his new book - Drawing Across Borders.

But why does a watercolor painting - made over an hour in just one location - matter in today’s age? Early in our conversation, I asked him about the relevance of illustrations in a time of multimedia coverage.

Listen to the episode for his deep thoughts on the subject.

For my part, I like to think of all visual media as containing packets of specific information. You can use words to convey the same information. But it would take a lot of words, and a lot of time, and still not be as effective as an image. While saying this, I also believe that today our minds are saturated by such recorded images - photos and videos. Special effects in movies have made explosions and scenes of complete devastation feel routine and boring.

Nothing shocks us anymore. Everyone has seen everything.

This is not the case with illustration. Every line and stroke of an illustration carries the deliberate intent, focus, and effort of an artist to depict what is in front of them. This makes it a personal account rendered at the location by the artist while feeling a certain way, thinking certain thoughts, and reacting to certain situations.

Because the information is incomplete, we fill in the blanks with our minds. Because it cannot be the absolute truth, it is reckoned with as someone's observation. A painting, then, has a greater impact upon us than a photo or video, because it pushes us to think, understand, and connect the dots.

George says that every illustration invites the active engagement of the viewer.

Through his work, he hopes to re-humanize peoples and places to whose conditions we have become desensitized.

Listen to our conversation on your choice of streaming service:

Spotify | Apple | PocketCasts | Google | Web | Gaana

Invading Afghanistan

(This portion of the post is not in the audio.)

I thought about speaking to George after reading William Dalrymple's fantastic book - Return of a King - about the 1st Anglo-Afghan War (1839-42). It tells the story of several British agents, soldiers, administrators, their allies, and their enemies. The book introduces us to many interesting personalities, but relevant to this post is a minor character who did not even have a speaking role.

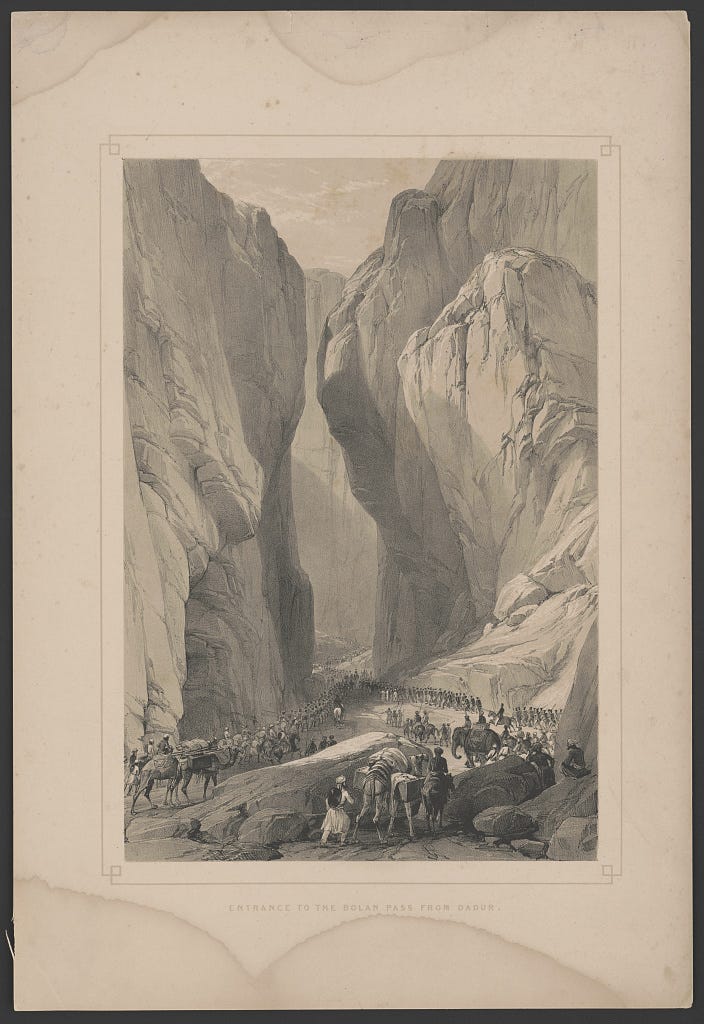

This was James Atkinson, a surgeon with the East India Company, who accompanied the army on its march into Afghanistan in 1839. He caught my eye because he made several illustrations on the way - depicting the terrain, people, camp-sites, and the city of Kabul (or Cabool as they called it).

Looking at these illustrations, I realized how this was the only way to communicate what the world looked like at that time. And today, as technology has taken us so far from this old world, this same illustration is the only way to imagine what the world looked like back then.

To put it simply, the First Anglo-Afghan War (1839-42) was a disaster. William Dalrymple describes it as the "greatest military humiliation ever suffered by the west in the east". When the British forces retreated from Kabul in Jan 1842, only one of the 18500 people who left the British cantonment, made it out six days later.

Here are some incredible comparisons between the First Anglo-Afghan War and the modern invasion of Afghanistan. I’ve taken these points from Dalrymple’s insightful articles on the subject - [1] [2].

- The tribal rivalries and local politics were exactly the same in exactly the same places, simply under new flags and ideologies. The British choice of king in 1839, Shah Shuja, belongs to the same tribe as Hamid Karzai, who was appointed in Afghanistan in the early 2000s. The principal opponents of the 1830s were the Ghilzais, who today make up the bulk of Taliban's foot soldiers.

- The First Afghan War was waged on the basis of doctored intelligence about a virtually non-existent threat and similar propaganda was shared to stifle opposition. John MacNeill, the British Ambassador, wrote - "We should declare that he who is not with us is against us. We must secure Afghanistan."

- The same cities were garrisoned by troops speaking the same languages, and they were attacked again from the same high passes. In both cases, the invaders thought they could walk in, change the regime, and exit quickly. In both cases, they were horribly wrong.

- Then as now, the poverty of Afghanistan has meant that it has been impossible to tax the Afghans into financing their own occupation. The East India Company treasury was depleted in occupying Afghanistan, just as the US has spent trillions of dollars to achieve no ends.

These are not fleeting comparisons. Afghans, historians, and even the Taliban were aware of the historical similarities.

“Everyone knows how Karzai was brought to Kabul and how he was seated on the defenseless throne of Shah Shuja,” the Taliban announced in a press release soon after he came to power.

Read this excellent article on different factors that make Afghanistan the graveyard of empires.

Return of a King reads like a historical action-thriller, and I recommend it to anyone interested in the subject. Considering the historical parallels, it may even be the best way to understand the paternalistic folly of Western "nation-building" in these parts of the world.

- How mass killings by US forces after 9/11 boosted support for the Taliban

Thank you for reading and listening! In the next issue, I will share some art and thoughts around drawing in Vancouver.